Installing an Application

In this lesson we will install our Curves program as a doubleclickable application.

First, load GrDemo as we described in Lesson 19. But this time, don't start it up.

Note for Mac OS X 10.4 users: To avoid a QuickDraw trouble Tiger users may need to modify grDemo source code a little in case of running Mach-O PowerMops. In file 'grDemo' you can find the definition of method

NEW:of classGRWIND(line 170). In the definition of the method, insert a line

$ 40000000 OR \ use QD on Tigerbetween lines '

RR tAddr tLen docWind' and 'true false'.That is, the last part of the method will look like following:

`RR tAddr tLen docWind \ initial rect, title, window type `$ 40000000 OR \ use QD on Tiger `true false \ visible, no close box `dView \ the main view `new: super \ create the window!Then save and (re)load the file.

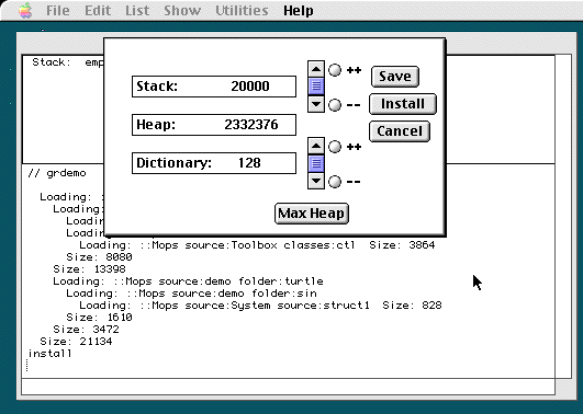

Either type install or select Install... from the

Utilities menu. Either way, this dialog box will appear:

Experiment with clicking in the controls. (Don't click the buttons yet).

You will see that if the Dictionary number increases, the Heap number

reduces by the same amount, and similarly for the Stack. You are here

defining how the available memory will be used in your application. The

'stack' space is for your parameter stack and your return stack. The

system will also use the parameter stack space when various system calls

are made, so we suggest you don't reduce this figure below

20000.

The Dictionary number refers to the amount of memory allocated for the dictionary, above what is allocated already. What we are doing now is installing an application which is already loaded, so that we won't need a very big number here, since no more definitions will be getting compiled into the dictionary when our application is running.

The Heap number refers to the memory that is available on request from the system, when your program is running. The number here is the maximum amount of this kind of memory that is available. Basically whatever is left over after the stack and dictionary space is allocated will be used for the heap. The number that appears here is only a guide, since when your installed application runs there might not be the same total amount of memory available as there was when you ran the install.<br /> It is good, then, to use only what you really require for the stack and dictionary, to make the best use of whatever memory is available when your application runs.

Normally what you'll do when installing an application is simply to leave the buttons alone. This will give you the maximum heap allocation as a default. If you've been clicking the buttons and changing the values, you can click the 'Max Heap' button to get back to the default settings.

You will see that the default stack allocation is

20000, which is the mimimum we recommend, and the

dictionary only 128. This just allows a safety margin

in case your application executes code that moves a string to

HERE. If you know that your application will need more

room at HERE, you can adjust this number. For the demo

program, however, there's no need.

Now that you have checked your memory requirements, click Install. You will get the following dialog. This will actually be the first dialog you'll get under PowerMops, and the PowerMops version also has an extra checkbox, 'Generate shared library', which we'll discuss later.

This dialog allows you to set your application's Creator code and File Types. These are both 4 character codes, and are described in detail in Inside Macintosh.

If you are going to release your application widely, you will need to register these codes with Apple as this avoids having different programs using the same code. For your private use, however, you can use any four letters of any case you like. For this demo program, Curves, we've chosen CRVS.

Curves will have no documents of its own, so leave the other boxes blank. Type the name of the application, Curves, in the appropriate box, and anything you for a 'version string'. In the example here, we've put 'version 1' which seems to make sense.<br /> The dialog box will now look like this:

We explained the 'start word' and the 'error word' in the last

lesson. The dialog suggests the names GO and

CRASH respectively, which are, in fact, the names of

the words we've used, so we can leave them unchanged.

The way these words are handled in an installed application is quite

simple, thanks to the mechanism of vectors, which we introduced in

lesson 20.<br /> A vector

is basically the same as what some Forth systems call a

DEFERred word. A vector contains an address. You call a

vector in the same way as for an ordinary word, but it is the word where

the address points which is actually executed. The address can be

changed at any time. The start word and the error word addresses are put

into two vectors, QuitVec and

AbortVec.

The (rather confusingly named) QuitVec is executed

whenever the word QUIT is executed, which is actually

at the start of each time around the Mops interpretation loop (the loop

that waits for keyboard input, then executes it). Normally

QuitVec does nothing (it points to

NULL), but in an installed application it is set to

point to the start word. This start word should loop indefinitely,

handling incoming clicks or whatever, and never terminate itself. Of

course the application will eventually terminate, but this should be in

response to some user action which is being handled by some word called

from the start word, which means the start word should not exit through

its ending semicolon. If it did, the rest of QUIT would

be executed, which would attempt to interpret keyboard input as Mops

words. This is definitely not what you want in an installed application

--- for one thing, the Mops window would probably not be there.

AbortVec is called when Mops detects an error that

normally gives a Mops error message. Like QuitVec it

initially points to NULL. In an installed application

you don't want your users to see a stack dump (and anyway the Mops

window, fWind, might not be there at all), so your error word should do

whatever is appropriate for your application, and perhaps then execute

BYE to quit to the Finder. Like the start word, it

shouldn't exit through its final semicolon, since that would lead to

Mops trying to give a Mops style error message and stack dump.

Now to continue with the dialog box. Leave 'Include fWind' and 'fWind visible' unchecked. These refer to a simple window for keyboard input and text output which can be used for "quick and dirty" applications. This is actually the window used by the basic nucleus before the rest of the Mops system is loaded. Curves makes no use of this window, since it has its own, so by leaving these boxes unchecked, we are telling Install that it can omit the resources for fWind. By the same arguement, we are not going to need the code generator in the installed application.

Now that all the relevant parts of the dialog have been filled in, click OK. Then a standard file navigation dialog will appear. Select a folder to install the applicaition in, then click Save. PowerMops will be quited immediately. Then if you now look in the folder you selected, you will find a new icon (68k Mops or PEF/CFM PowerMops) or folder (Mach-O PowerMops) named 'Curves'.<br /> This is your installed application.

But the application still isn't ready to run, since the menu resources haven't been included in it.

68k Mops and CFM/PEF PowerMops:<br /> This can be done with a resource editor. Start ResEdit or other resource fork editor and open demo.rsrc, or just double-click demo.rsrc. Do 'Select All', then Copy. Then (still in ResEdit), open Curves, and do Paste. Then choose Save to save the updated copy of Curves, and quit ResEdit.

Mach-O PowerMops:<br /> Create a copy of demo.rsrc on Finder, and put it (named as demo.rsrc) in 'MacOS' folder in the created application folder structure. Then add '.app' extension to the folder name 'Curves'.

Your new application still won't have a proper icon, it will have just the generic 'application' icon but otherwise it is finished. You can doubleclick it and run it.<br />We will discuss icons later in part II, chapter 5.

Where To Go From Here

You've already had quite an exposure to Mops and object oriented programming. You've seen how Mops interacts with the Macintosh Toolbox to simplify the way your programs communicate with the Mac.

Now, it's time for you to start experimenting with programs of your own. Several chapters in Part II should point you in the right direction with details of the finer points of Mops programming on the Macintosh.

It is important that you have an acquaintance with the powers of the predefined classes and the words in the Mops dictionary. While there is more to it than a casual reading will ever reveal, you should spend some time studying the methods of the predefined classes as detailed in Part III of this manual to discover what building blocks are available to you.

You should also browse through the Mops Index and Glossary in Part IV, where you'll likely discover many built-in words that give you ideas about the operations you can specify for methods.

A vast amount of reference material is available in this manual and in the various Mops files. The best way to make use of it all is to start defining some classes on your own and experiment sending messages to the objects you create.

Just as with a spoken language, the more you practice with Mops the faster You'll be comfortable with it.